#5 The Agents You Never Knew About

You’ve probably never heard of them, but the farmer who grows your food has.

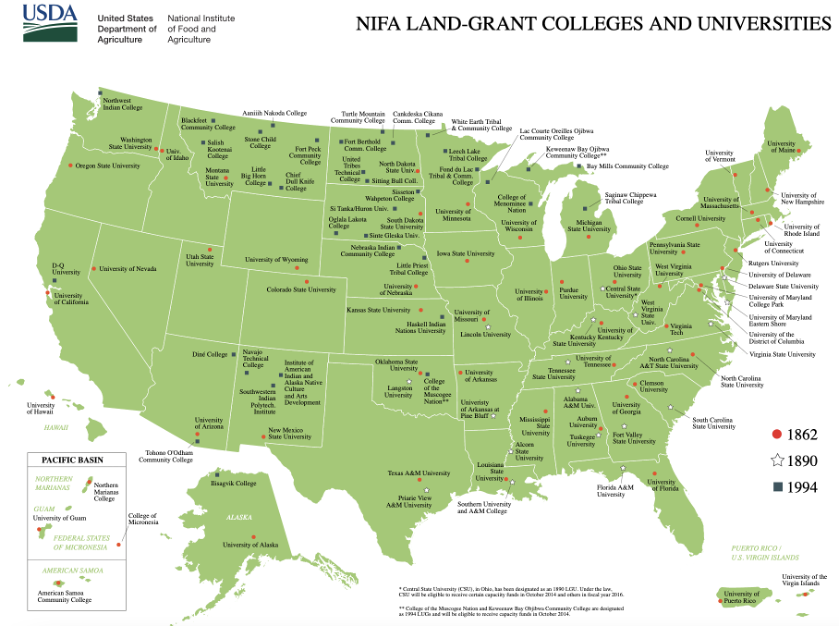

The Big Picture: In 1862, the U.S. Government created land-grant institutions through the Morrill Act. This provided land and funds to States to create colleges focused on developing farming and mechanical skills for working-class Americans.1 Then, in 1914, the Smith-Lever Act formalized the Cooperative Extension System (CES) with each land-grant university to disseminate agricultural research and education to farmers nationwide.

Meet the Cooperative Extension Agents.

You’ve probably never heard of them, but the farmer who grows your food has. They provide farmers with educational programs and support, connect them to local markets, help them find local consumers, and work to increase their economic and environmental sustainability and resiliency.

One hundred years later, the CES and its agents have facilitated America’s agricultural revolution. The produce you eat today was grown on a farm somewhere in America made possible by the guidance provided by these agents and research done by a land-grant university.

Cooperative Extension in Mid-Florida

In Orlando, I visited the University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Mid-Florida Research & Education Center (MREC) to learn more about the Extension’s role here in my home state. I sat down with Dr. Liz Felter, a regional specialized agent in Extension for food systems and ornamental production industry, and Dr. Catherine Campbell, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Family Youth and Community Sciences and State Extension Specialist in Community Food Systems.

A mouthful, but stay with me.

Their mission is to support Florida farmers through research, education, and training. However, it’s not only the farmers they’re helping: it’s policymakers, developers, and you, the consumer. Together, Felter and Campbell are working to provide clear guidelines to policymakers on how to establish urban agriculture production and city policy.

In Florida, this is critical. Florida’s population grew from 18.8 million residents in 2010 to 21.5 million in 2020.2 More people mean more mouths to feed. For Dr. Felter and Dr. Campbell, this means ensuring that developers are building new communities that account not only for food distribution, e.g., a grocery store, but also for food production.

New housing and development are critical but failing to incorporate food production as part of this urban ecosystem is not how a city builds food and agriculture resilience. The sad thing is, most Floridians don’t understand that, hence why Dr. Campbell’s work is critical for the future of agriculture inclusion in city development.

Protecting farmland is one solution. Incorporating farms into new and old developments is another.

We’re seeing this with agrihoods and other large-scale residential developments, such as The Villages Grown. The Villages in Sumter County, Florida, have slotted 45 acres of land for farming and currently have 5 acres of greenhouse production. This was "driven by the fact that in a survey the residents of the Villages noted the number one thing they wanted was to have their own local produce available to them. So, there's a huge population there that wants fresh locally grown produce," says Dr. Felter. This social science element of agriculture—consumer preference—is important for farmers to understand. Locally grown, pesticide-free, higher-nutrition, and longer shelf life are what consumers want.

As the need for more local farms grows, so does the necessity of feasibility studies. Farms are businesses, and like every business, they need a plan for profitability. Felter notes that The Villages Grown success stems from conducting extensive resident outreach, e.g., figuring what your customer wants and at what price point they will purchase and then meticulously planning how best to grow those crops before investing millions of dollars into capital expenditures.

Increasing awareness about farming and different types of agriculture in the classroom is crucial. When looking at this gap between the consumer and farmer, it’s disturbing to see how few people work in agriculture. According to the USDA, it’s less than 2% of the workforce.

Training the next generation of farmers and workers in agriculture is well recognized as a key issue in the agricultural industry, especially in controlled environment agriculture (CEA). For agriculture Extension agents, providing education and training is part of their everyday responsibilities. Dr. Felter has been teaching pest identification and plant disease, as part of integrated pest management (IPM), for over 25 years now.

“We talk about insects, diseases, water quality, and weed control… We're seeing people don't understand the chemistry behind the [nutrient] solution. That means they don't understand what symptoms plants will exhibit when they're nutrient deficient or overdosed,” says Dr. Felter.

It's not just plant science, plant nutrition, and IPM that farmers need to know. This next generation of farmers needs to have some engineering or mechanical background. In a greenhouse, vertical farm, or soil-based farm, if a mobile tray, pump, or machine breaks, you need to understand the mechanics of your system in order to fix it.

A combination of horticulture and engineering skills is the right mix for the next generation of farmers. Add in leadership skills, management experience, accounting, communication, and observation skills, and you have one ideal candidate.

“This is an area that makes me wonder how hard it will be to find people who want to do the engineering and have the soft skills,” says Dr. Campbell.

The classes Felter teaches bring together individuals from all different backgrounds: political science, religion, and even philosophy. Felter has noticed in these classes that regardless of academic degrees, those passionate about learning tend to be successful. And while the passion is inspiring and motivating, the reality is that we, as a country, have not done enough to support our farmers.

The CEA Opportunity in Florida

States and cities will need to take significant steps to bolster their food and agriculture infrastructure. Whether it's a pandemic, hurricane, supply chain issue, or population increase, relying on out-of-state or non-local farms to feed communities is high risk. For local farmers, it's high reward. Building more local farms and increasing the number of local farmers will take a combination of policy changes, workforce development, and education across all parts of the agricultural supply chain.

Here in the Sunshine State, heat, humidity, and weather are problems. The controlled environment that greenhouses provide can extend the growing season for the farmer. While soil-based farms may struggle to effectively grow certain crops (e.g., lettuce, a cold-weather crop) during the summer, CEA can grow and offer consumers fresh produce almost year-round.

Ag extension agents such as Dr. Felter and researchers such as Dr. Campbell are here to help.

Extension in the News!

Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation Establishes Tribal Department of Agriculture - UConn Extension offers assistance in developing sustainable agriculture and community education

How Vermont Became an Unlikely Hotbed for Saffron - University of Vermont Extension is leading the way in saffron research for the Northeast

A second Morrill Act was passed in 1890 to address educational inequality among African Americans and Native Americans.